tracing tokio tasks

by on Friday, 29 September 2023

Async programming can be tricky.

Part of the reason for this is that your program is no longer linear.

Things start.

Then they pause.

Something else runs.

It pauses.

The first thing starts again.

The second thing runs.

Then it finishes.

Then the first thing pauses again.

What a mess!

It would be nice if we had a way to analyse what's going on.

Even if it's after the fact.

The good news is you can!

(the not so good news is that the visualisation could be improved)

How is this possible?

Tokio is instrumented!

(I'm talking about Tokio because I'm familiar with it)

(there are many other async runtimes for Rust which may also be instrumented)

(although I don't know of any)

Parts of the Tokio codebase are instrumented with Tracing.

We're going to look specifically at tracing tasks in this post.

Although more of Tokio is also instrumented.

aside: tracing

Tracing is really an ecosystem unto itself.

At the core, Tracing is all about recording spans and events.

An event is something that happens at a specific moment in time.

(traditional logging is all events)

A span represents a period in time.

It doesn't have a single time.

It has two.

The start time and the end time.

(small lie, more on this later)

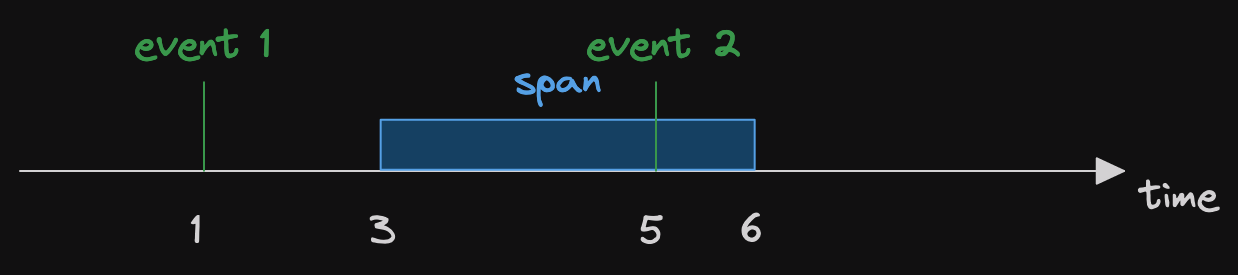

Let's look at a picture to illustrate the concept.

Here we can see two events and a span.

(in a very simplistic visualisation)

The first event occurs at time=1.

(it is cleverly named event 1)

Then we have a span which starts time=3 and ends at time=6.

Within the span we have another event that occurs at time=5.

So we see that events can occur within the context of a span.

Spans can also occur within other spans.

Why do we care?

fields

Traditional logging frameworks generally take two pieces of input for a given log.

The level.

(error, warn, info, debug, trace, and maybe more)

The message.

(some blob of text)

It is then up to whatever aggregates the logs to work out what is what.

(often the whatever is a person staring at their terminal)

This made sense when you log to a byte stream of some sort.

(a file, stdout, etc.)

However we often produce too many logs for humans now.

So we want to optimise for machine readability.

This is where structured logging is useful.

Rather than spitting out any old text and then worrying about format when ingesting it.

We can write logs that can be easily parsed.

To illustrate, let's look at an example of non-structured logs.

I stole this example from a Honeycomb blog post.

Jun 20 09:51:47 cobbler com.apple.xpc.launchd[1] (com.apple.preference.displays.MirrorDisplays): Service only ran for 0 seconds. Pushing respawn out by 10 seconds.

Now let's reimagined this line as a structured log.

(again, courtesy of the good folk at Honeycomb)

{"time":"Jun 20 09:51:47","hostname":"cobbler","process":"com.apple.xpc.launchd","pid":1,"service":"com.apple.preference.displays.MirrorDisplays","action":"respawn","respawn_delay_sec":10,"reason":"service stopped early","service_runtime_sec":0}

This isn't so readable for you.

But it's so much more readable for a machine.

Which brings us back to fields.

Tracing events and spans have fields.

So that the other side of the ecosystem can output nice structured logs.

(the other side generally being something built with tracing-subscriber)

Or even send them to distributed tracing system.

So you can match up what this machine is doing with what some other machines are doing.

And that's the great thing about spans.

A span's children effectively inherit its fields.

So if you set a request id on a span.

(for example)

Then the children spans and events will have access to it.

How that is used is up to the subscriber.

span lifecycle

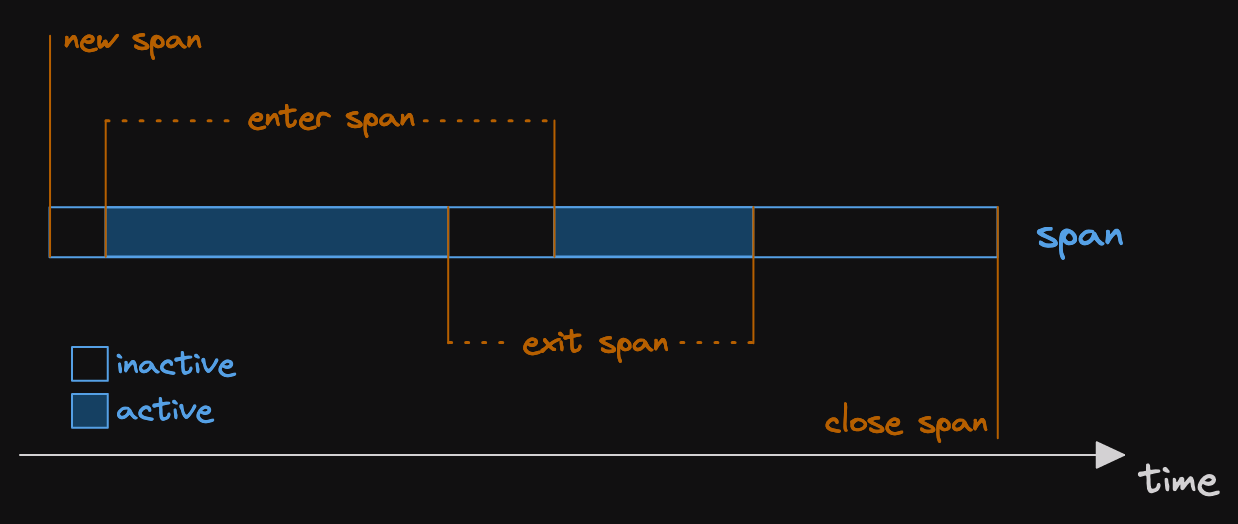

It's now time to clear up that little lie.

The one about spans having a start and end time.

In Tracing, a span has a whole lifecycle.

It is created.

Then it is entered.

(this is when a span is active)

Then the span exits.

Now the span can enter and exit more times.

Finally the span closes.

The default fmt subscriber can give you the total busy and idle time for a span when it closes.

(that's from the tracing-subscriber crate)

(use .with_span_events() to enable this behaviour)

Later you'll see why knowing about span lifecycles is useful.

tracing our code

As I mentioned at the beginning, Tokio is instrumented with Tracing.

It would be nice to see what's going on in there.

So let's write a very small async Rust program.

And look at the instrumentation.

The code is in the web-site repo: tracing-tokio-tasks.

We'll start with Cargo.toml

[package]

name = "tracing-tokio-tasks"

version = "0.1.0"

edition = "2021"

[dependencies]

tokio = { version = "1.32.0", features = ["full"] }

tracing = "0.1.37"

tracing-subscriber = "0.3.17"

Pretty straight forward list of dependencies.

(I'm including the exact version here, which isn't common)

(but hopefully helps anyone following along in the future)

We're looking at tokio, so we'll need that.

We want to use tracing too.

And to actually output our traces, we need the tracing-subscriber crate.

Now here's the code.

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() {

// we will fill this in later!

tracing_init();

tokio::spawn(async {

tracing::info!("step 1");

tokio::time::sleep(std::time::Duration::from_millis(100)).await;

tracing::info!("step 2");

})

.await

.expect("joining task failed");

}

OK, let's dig in.

We're using #[tokio::main] so we're in an async context from the beginning.

We set up Tracing.

(we'll get into exactly how later)

Then we spawn a task.

Before we look at the contents of the task, look down.

We're awaiting the join handle returned by spawn().

(so the task has to end before our program quits)

Now back into the task contents.

We record an event with the message "step 1".

(it's at info level)

Then we async sleep for 100ms.

Then record another event.

This time with the message "step 2".

tracing init

Let's write a first version of our init_tracing() function.

fn tracing_init() {

use tracing::Level;

use tracing_subscriber::{filter::FilterFn, fmt::format::FmtSpan, prelude::*};

let fmt_layer = tracing_subscriber::fmt::layer()

.pretty()

.with_span_events(FmtSpan::FULL)

.with_filter(FilterFn::new(|metadata| {

metadata.target() == "tracing_tokio"

}));

tracing_subscriber::registry().with(fmt_layer).init();

}

Both the tracing and tracing-subscriber crates have extensive documentation.

So I won't go into too much depth.

We're setting up a formatting layer.

(think of a tracing-subscriber layer as a way to get traces out of your program)

(out and into the world!)

The fmt layer in tracing-subscriber will write your traces to the console.

Or to a file, or some other writer.

The fmt layer is really flexible.

We're going to use some of that flexibility.

We want .pretty() output.

This is a multi-line output which is easier to read on a web-site.

(I never use this normally)

The call to .with_span_events() won't do anything just yet.

(so we'll skip it now and discuss later)

Finally we have a .with_filter().

For now we only want the events from our own crate.

(that was simple, right?)

Let's look at the result.

2023-09-27T13:46:56.852712Z INFO tracing_tokio: step 1

at resources/tracing-tokio-tasks/src/main.rs:29

2023-09-27T13:46:56.962809Z INFO tracing_tokio: step 2

at resources/tracing-tokio-tasks/src/main.rs:33We have logs for each of our two events.

And they're roughly 100ms apart.

(it's actually more like 110ms)

(I wonder where that time went?)

OK, let's start tracing something inside Tokio.

There are a few things we have to do here.

-

include task spawn spans in our filter

-

enable the

tracingfeature in tokio -

build with the

tokio_unstablecfg flag

The filter is straight forward.

To include the spans, we update the filter.

Our fmt layer creation will now look like the following.

let fmt_layer = tracing_subscriber::fmt::layer()

.pretty()

.with_span_events(FmtSpan::FULL)

.with_filter(FilterFn::new(|metadata| {

if metadata.target() == "tracing_tokio" {

true

} else if metadata.target() == "tokio::task" && metadata.name() == "runtime.spawn" {

true

} else {

false

}

}));

Which is to say.

We also accept traces with the target tokio::task.

But only if the span's name is runtime.spawn.

(and therefore, only if it's a span)

(events don't have names)

Now let's add the tracing feature.

This is as simple as modifying the tokio line in Cargo.toml.

tokio = { version = "1.32", features = ["full", "tracing"] }

Finally, tokio_unstable.

aside: tokio_unstable

Tokio takes semantic versioning seriously.

(like most Rust projects)

Tokio is now past version 1.0.

This means that no breaking changes should be included without going to version 2.0.

That would seriously fragment Rust's async ecosystem.

So it's unlikely to happen.

(soon at any rate)

But there's an escape hatch: tokio_unstable.

Anything behind tokio_unstable is considered fair game to break between minor releases.

This doesn't mean that the code is necessarily less tested.

(although some of it hasn't been as extensively profiled)

But the APIs aren't guaranteed to be stable.

I know of some very intensive workloads that are run with tokio_unstable builds.

So, how do we enable it?

We need to pass --cfg tokio_unstable to rustc.

The easiest way to do this is to add the following to .cargo/config in your crate root.

[build]

rustflags = ["--cfg", "tokio_unstable"]

(needs to be in the workspace root if you're in a workspace)

(otherwise it won't do nuthin')

Back to tracing!

tracing tasks

Each time a task is spawned, a runtime.spawn span is created.

When the task is polled, the span is entered.

When the poll ends, the span is exited again.

This way a runtime.spawn span may be entered multiple times.

When the task is dropped, the span is closed.

(unless the task spawned another task)

(but that's actually incorrect behaviour in the instrumentation)

If you want to understand what polling is, I have a blog series for that.

(check out how I finally understood async/await in Rust)

We'd like to see all these steps of the span lifecycle in our logs.

Which is where span events come in.

By default the fmt layer doesn't output lines for spans.

Just events and the spans they're inside.

Span events are the way to get lines about spans themselves.

Specifically, events for each stage of a span's lifecycle.

(new span, enter, exit, and close)

We enable span events using .with_span_events(FmtSpan::FULL) as seen in the original code.

Now we're ready!

Let's see the output we get now.

2023-09-28T12:44:27.559210Z TRACE tokio::task: new

at /Users/stainsby/.cargo/registry/src/index.crates.io-6f17d22bba15001f/tokio-1.32.0/src/util/trace.rs:17

in tokio::task::runtime.spawn with kind: task, task.name: , task.id: 18, loc.file: "resources/tracing-tokio-tasks/src/main.rs", loc.line: 32, loc.col: 5

2023-09-28T12:44:27.567314Z TRACE tokio::task: enter

at /Users/stainsby/.cargo/registry/src/index.crates.io-6f17d22bba15001f/tokio-1.32.0/src/util/trace.rs:17

in tokio::task::runtime.spawn with kind: task, task.name: , task.id: 18, loc.file: "resources/tracing-tokio-tasks/src/main.rs", loc.line: 32, loc.col: 5

2023-09-28T12:44:27.574405Z INFO tracing_tokio: step 1

at resources/tracing-tokio-tasks/src/main.rs:33

in tokio::task::runtime.spawn with kind: task, task.name: , task.id: 18, loc.file: "resources/tracing-tokio-tasks/src/main.rs", loc.line: 32, loc.col: 5

2023-09-28T12:44:27.588111Z TRACE tokio::task: exit

at /Users/stainsby/.cargo/registry/src/index.crates.io-6f17d22bba15001f/tokio-1.32.0/src/util/trace.rs:17

in tokio::task::runtime.spawn with kind: task, task.name: , task.id: 18, loc.file: "resources/tracing-tokio-tasks/src/main.rs", loc.line: 32, loc.col: 5

2023-09-28T12:44:27.683745Z TRACE tokio::task::waker: op: "waker.wake", task.id: 1

at /Users/stainsby/.cargo/registry/src/index.crates.io-6f17d22bba15001f/tokio-1.32.0/src/runtime/task/waker.rs:83

2023-09-28T12:44:27.690542Z TRACE tokio::task: enter

at /Users/stainsby/.cargo/registry/src/index.crates.io-6f17d22bba15001f/tokio-1.32.0/src/util/trace.rs:17

in tokio::task::runtime.spawn with kind: task, task.name: , task.id: 18, loc.file: "resources/tracing-tokio-tasks/src/main.rs", loc.line: 32, loc.col: 5

2023-09-28T12:44:27.710193Z INFO tracing_tokio: step 2

at resources/tracing-tokio-tasks/src/main.rs:37

in tokio::task::runtime.spawn with kind: task, task.name: , task.id: 18, loc.file: "resources/tracing-tokio-tasks/src/main.rs", loc.line: 32, loc.col: 5

2023-09-28T12:44:27.716654Z TRACE tokio::task: exit

at /Users/stainsby/.cargo/registry/src/index.crates.io-6f17d22bba15001f/tokio-1.32.0/src/util/trace.rs:17

in tokio::task::runtime.spawn with kind: task, task.name: , task.id: 18, loc.file: "resources/tracing-tokio-tasks/src/main.rs", loc.line: 32, loc.col: 5

2023-09-28T12:44:27.723284Z TRACE tokio::task: close, time.busy: 46.9ms, time.idle: 117ms

at /Users/stainsby/.cargo/registry/src/index.crates.io-6f17d22bba15001f/tokio-1.32.0/src/util/trace.rs:17

in tokio::task::runtime.spawn with kind: task, task.name: , task.id: 18, loc.file: "resources/tracing-tokio-tasks/src/main.rs", loc.line: 32, loc.col: 5Purple, wow!

(actually magenta)

What is new here is that there is a new span.

It has the target tokio::task.

The span also has a name, runtime.spawn.

(remember, this is how we're filtering for these spans)

Because we enabled span events, we can see the span lifecycle.

The lifecycle state is at the end of the first line of each span event message.

Here is an enter event: TRACE tokio::task: enter

We also have another event with the target tokio::task::waker

The waker events are a bit verbose.

So I've manually removed all the ones that don't have op=waker.wake.

(if you're interested in this, the other op values are waker.clone and waker.drop)

There is something important about this waker.wake event.

It is not inside the task span!

(more on that later)

And of course, our two previous events are still there.

But now they're inside the runtime.spawn span!

This means that from the logs, we could check which task they've come from!

It's the task with Id=18.

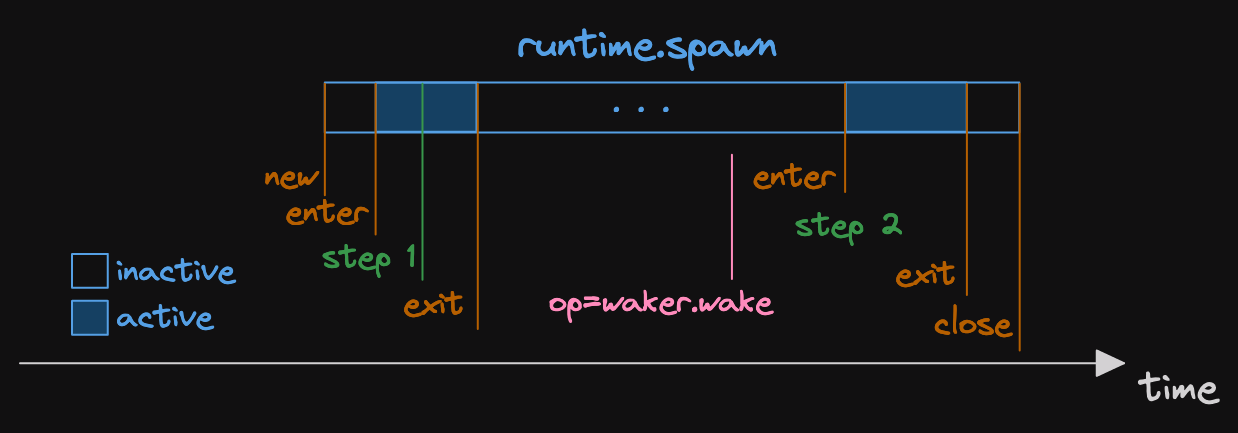

We can visualise the spans and events in this trace.

First thing to note about this diagram.

It's not to scale!

(that's what the dots in the span mean)

But that doesn't matter, it's illustrative.

(you shouldn't create diagrams like this for production logs)

(it's incredibly laborious)

(but I haven't found a way to automatically create pretty diagrams from tracing output)

What we can see is that we have a span which is relatively long.

And it has two much smaller active sections.

Within each of these sections, we emit an event.

(remember, our cleverly named step 1 and step 2)

This shows us that the task was polled twice.

And we see that the op=waker.wake event isn't in the runtime.spawn span.

This means that the task didn't wake itself.

It was woken by something else.

(which is enough information for now)

calculation the poll time

We can calculate the poll times!

Just look at the difference between the enter and exit events.

So the first poll took around 20ms.

The second poll took around 26ms.

That's interesting, I wonder why the second one took longer?

(I wonder why they're taking so long at all)

(20ms is a really long time!)

calculating the scheduled time

We can also calculate the scheduled time for the second poll.

That's the time between when it was woken and when it was polled.

(I wrote a post about the scheduled time)

(related to some tool, which I won't mention here to not spoil the end)

So, let's calculate the scheduled time.

Let's find the wake time for our task.

We know it's the one with task.id=18.

But we only see a single waker.wake event.

And it has task.id=1.

What is going on here?

It turns out, there's some inconsistency in the Tokio instrumentation.

The meaning of the field task.id has different meanings in different contexts.

When used on runtime.spawn span, it means the tokio::task::Id.

But when used on a waker event, it refers to the tracing::span::Id of a runtime.spawn span.

This is unfortunate and a bit confusing.

More so because the fmt layer doesn't have the option to output the span Id.

It's considered internal.

(and why parsing these traces "manually" isn't recommended)

But anyway, in this case there's only one task, so we know which one it is.

So we calculate the scheduled time as around 6ms.

This is pretty high too.

Especially because our runtime isn't doing anything else.

There's something weird going on here.

the mystery of the delay

Why do we have these large amounts of time between operations?

(yes, 20ms is a large amount of time)

(if you don't believe me, please see Rear Admiral Grace Hopper explaining nanoseconds)

It turns out it's all my fault.

The code in the examples is missing something.

It's not the code that was run to produce the output snippets.

I wanted to show the colourised output that you get in an ANSI terminal.

So I wrapped the pretty FormatEvent implementation with another writer.

This HtmlWriter takes the output and converts ANSI escape codes to HTML.

Fantastic!

Now I have pretty output on my web-site.

But it's very slow.

The fmt layer writes bytes out.

These have to be read into a (UTF-8) &str and then get converted.

Which requires another copy of the data.

Then it's all written out.

My bet is that something in the ansi_to_html crate is slowing things down.

(but only because I tried using str::from_utf8_unchecked and it didn't help)

And that's all the resolution you're going to get today I'm afraid.

Maybe another day we can profile the writer to see what is actually so slow.

When I disable the custom writer, it's a very different story.

There is less than 700 microseconds of busy time for the runtime.spawn span.

Whereas in the example above, there are more than 46 milliseconds of busy time.

don't do this at home

Reading the traces produced by Tokio like this isn't advisable.

Even this trivial example produces a lot of output.

Instead you should use something to analyse this data for you.

And show useful conclusions.

And there's a tool for that.

It's Tokio Console.

I've mentioned it in other posts.

Another option would be to have direct visualisation of the traces.

Unfortunately, I haven't found anything that does this well.

(hence the magnificent hand drawn visualisation used in this post)

If you know of something, I would love to hear from you.