commit message rant (part 1 of n)

by on Monday, 18 March 2024

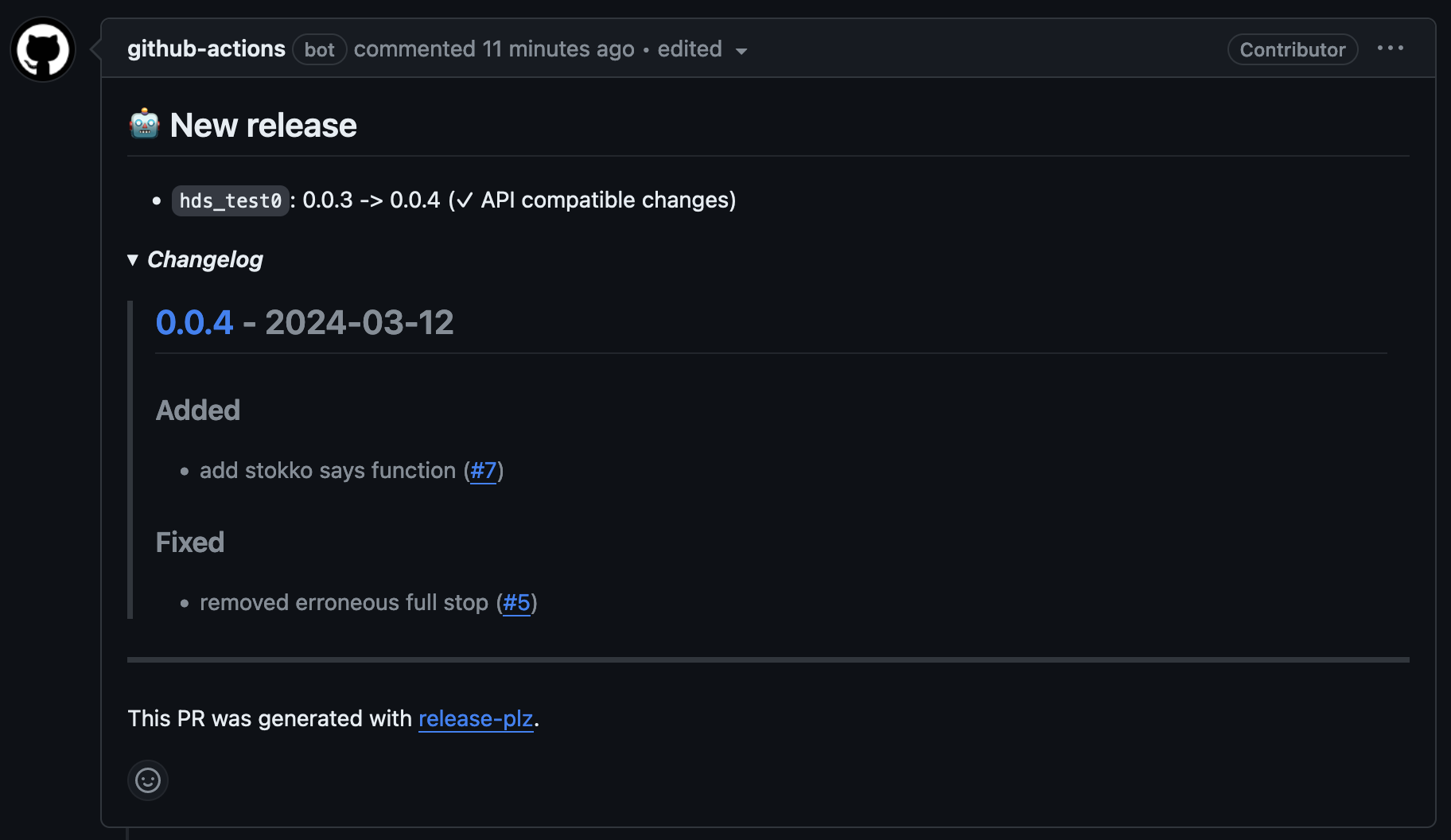

The other day I was setting up release automation for a Rust project. Everything was going great and I'm happy with the release tooling I'm trying out. Then it got to creating the release PR. This looks great, it includes all the information about the release. The version that's being released, a changelog (which is customizable), as well as a link to the commits in the latest version. Here's an example from a test project:

Fantastic, all the information that I need in one place. A summary of the changes that have gone into the release as well as the version number that these changes will be released with. Then I go to the subsequent commit message and it looks like this:

chore: release (#6)

Signed-off-by: github-actions[bot] <41898282+github-actions[bot]@users.noreply.github.com>

Co-authored-by: github-actions[bot] <41898282+github-actions[bot]@users.noreply.github.com>

All that wonderful information, all that rich context, gone! Blown away onto the wind. Or rather, trapped in a dark room with a door that only sort of works (see but it's already somewhere else and the tooling is fighting you).

Now is the part where I have to apologise to Marco Ieni, the author of the fantastic release-plz project. I don't want to take aim at Marco specifically, it was just that this experience perfectly highlighted the general trend to not include important information in commit messages.

Note to self: open an issue on release-plz to include more detailed information in the commit message. (done: #1355)

rant

This rant is a long time coming, and it may be the first of many, but it might be a bit, ... ranty. Don't say I didn't warn you.

These days, I would wager that a very large percentage of the readers of this site use Git, for better or worse it has become ubiquitous in much of the industry and perhaps even more so in the open source world. I'm going to use Git as an example throughout this post, but everything I say applies to every other source code management / version control system that is worth using. I'd even go so far as to say that any system that doesn't allow the sort of access to commit messages that I'll describe is actively working against your best interests.

Commit messages are the most durable store of information that any software project has. When you clone (or checkout) a project, the commit messages are right there. Every member of your team has a local copy. Accessing commit messages is simple and extracting them from the rest of the repository is not much more complicated.

So why would you waste this fantastic store of information with commit messages like:

Fix NullPointerException

Sorry! This is a Rust blog:

Fix unwrap panic

You may laugh and say no one ever does this. But I ran a search on a private GitLab instance I have access to and found 2.5K commits where the message was some variation of this with no more information! Interestingly I found a few results for "panic" as well, but the results were a little more varied (some of them were related to aborting on panic and many more related to terraform). Still, very few had any actual commit message. Part of the fault of this is GitLab itself, but we'll go into that later (the tooling is fighting you).

This isn't very useful, I could probably work out for myself that a NullPointerException

what should a commit message contain?

In one word: context.

This topic was covered wonderfully by Derek Prior (the principal engineering manager at GitHub, not the fantasy book author by the same name) in his 2015 RailsConf talk Implementing a Strong Code-Review Culture. If you haven't seen that talk, it is well worth watching.

To summarise, a commit message should contain the why and the what. Why was a change necessary? Why was it implemented the way it was? Why were those tools used chosen? What was changed? What benefits and and down-sides does the implementation have? What was left out of this particular change? (and why?)

If you're the sort of person who writes a single line summary and leaves it at that (we've all been that person), start by making yourself write two paragraphs in the body of the commit message for every commit. (1) Why was this change made. (2) What does this change do.

And all of this should be in the commit message. (want to see an example?)

You should also definitely link the issue, ticket, or whatever it is that you use to prioritize work. But that is part of the why, not all of it.

And yes, I can hear many of you saying...

but it's already somewhere else!

There are people screaming, this is already written down! It's in the ticket! It's in the Pull Request description! It's written on a sticky note on the side of the server! (you'd be surprised)

I'm sure you have this information written down, but there are two reasons why the commit message is a much better place for this information - even if that means duplicating it.

The first is persistence. As mentioned above, commit history is a distributed store of information, there are redundant copies on every developer's machine. It doesn't matter if you lose your internet connection, you've still got the commit history and all those wonderful commit messages.

Your ticketing system does not have these properties. GitHub (or GitLab or Codeberg) does not have these properties.

I've seen JIRA projects get deleted for all sorts of reasons.

- "It's confusing keeping this old project around, people will create tickets for us there, let's just delete it."

- "We're migrating to a new instance with a simpler configuration, migrating all the tickets is too complex, it's better to start afresh."

- "JIRA is too complex, we're moving to a simpler solution that covers all our needs, no, we can't import our closed tickets."

GitHub has been a staple of open source development for a decade and a half now. But many open source projects have lived much longer than that. GitHub won't be around for ever, and when it comes time to migrate to whatever solution we find afterwards, pulling all the PR and Issue descriptions out of the API is likely to be something that many maintainers simply don't have time for.

I challenge you to find a semi-mature engineering team that will accept migrating to a new version control system that doesn't allow them to import their history from Git/Mecurial/SVN/...

Keeping that valuable information behind someone else's API when you could have it on everyone's development machine seems crazy.

The second reason is cognitive. There is no person in the history of time and the universe who understands a change better than the you who just finished writing it and runs git commit. So this is the person who should describe the changes made. Not the Product Owner who wrote the user story, not the Principal Engineer who developed the overall architecture, you the developer who just finished writing the code itself. And it's probably all right at the front of your head as well, ready to be spilled out into your text editor.

If you amend your commit as you work, then you can amend the message as well, keeping it up to date with the changes in that commit. If you prefer to develop in separate commits, then ensure that each commit contains a full picture of the code up until that point. You don't want to be scratching your head trying to remember why you picked one of three different patterns for that one bit of logic you wrote last week.

A Pull Request description has many of these benefits, but it lacks the persistence and accessibility as mentioned above.

the tooling is fighting you

Like all those social media and app store walled gardens that we love to hate, source code management software and ticketing systems want to lock you in.

Aside from the obtuse APIs they often provide to access this data, some of them are actively "forgetting" to add important information to merged commit messages.

GitHub encourages you to add your commit message as the PR description - but only the first commit when the PR is created. Then the default merge (as in merging a branch) message contains none of that PR description - so you're left with whatever development history the branch has. And "Fixed tests" is not a useful commit message to find anywhere.

At least GitHub squash merges include all the commit messages of the squashed commits by default (as little use as that often is). By default, when GitLab creates a squash merge it will include the summary taken from the Merge Request title and then for the message body: nothing at all! This is actually one of the reasons why my search results turned up so many commits with no message body.

Ironically (because people love to hate it), Gerrit is the one piece of source code management software that does commit messages correctly. Commit messages show up as the first modified file in a changeset. The commit message can be commented on like any changed file. When the merge occurs, the commit message that has been reviewed is what gets included.

Linking to a ticket (issue) is a good idea. But also mention other tickets related to previous or upcoming changes that the implementation had to take into consideration. When you lose access to those tickets, this extra information can help find other relevant changes as your poor successors (maybe including future you) are going about software archaeology.

show me an example

Let's looks at an example.

BLAH-2140: Use least request balancing

We have a ticket number, so maybe there's some useful information there. Oh, too late, the ticketing system was migrated 3 years ago, we didn't keep old tickets.

Wouldn't it be better if we had a bit more context?

BLAH-2140: Use least request balancing in Envoy

We had reports of latency spikes from some customers (BLAH-2138). The

investigation led to us noticing that the Info Cache Service (ICS) pods

did not appear to be equally loaded.

As our front-end pods communicate with the ICS pods via gRPC, we perform

client side load balancing using Envoy Proxy

(https://www.envoyproxy.io/) as native Kubernetes load balancing doesn't

support HTTP/2 (see investigation in BLAH-1971).

Since our incoming requests often require significantly different

processing time on the ICS pods, the round robin load balancer in

Envoy was overloading some pods. The documentation suggests that in

this case, using the least request strategy is a better fit:

https://www.envoyproxy.io/docs/envoy/v1.15.5/intro/arch_overview/upstream/load_balancing/load_balancers

The experimental testing we performed confirmed this configuration.

The results are available at:

https://wiki.in.example.com/team/ics/load-balancer-comparison/

This change switches the load balancing strategy used in Envoy sidecar

container (in the trasa pods) to use weighted least request.

First, we make our summary a little more descriptive. We're using Envoy for load balancing, let's have that right up there.

Then we start with the reason why we're making any change at all, we've had bug reports and we found a problem. Following that, we have a bit of history. This will save anyone who is reading the commit message having to go hunting down the reason we're even using Envoy. Note that when we say that we're using some software, we link to the web-site. This isn't a lot of work and provides clarity in case some other Envoy software exists in 3 years time.

Now we describe the approach chosen. We link the documentation that we read as justification for our change - and we link to the version we're using and not latest! We follow this by explicitly stating that experimental testing was performed (this removes the doubt in the reader's mind that this change was shipped to be tested in production) and we link to our internal wiki for that.

At the end, we describe what has been changed. This paragraph is short in this case, because the change itself is only one line, if your change is more complex, you may want to spend more time summarising it.

While this may look like a large description for what is ultimately a small change, the effort involved in deciding on the change was significant. And that's the key, the metric for deciding upon how descriptive a commit message should be is the time taken to come to the right solution, not the number of lines changed.

signing off

Some code review platforms like to add meta information to the commit message. For example, listing the authors of different commits that went into a reviewed change, or the names of the reviewers.

This might be useful, but naming names is the least valuable information (and is usually hiding the fact that the knowledge those named have isn't properly transferred to the commit message itself).

In my mind, the the real reason to call it git annotate instead of git blame is that the person it wrote a change is the least interesting thing. It's all the context that should be included in a good commit message which is going to annotate your code.

the end (for now)

Commit messages are an important part of communicating with developers who will work on a code base in the future. They are far more robust that than most other stores of information (tickets, wikis, etc.).

Next time you don't write a detailed, useful commit message, think about what those 5 minutes you saved is going to cost someone in the future.